Overture to the opera Semiramide by Gioacchino Rossini

Continuing with our survey, our next orchestral excerpts are from Semiramide. Rossini really liked our instrument! The interesting fact is that we do not find so frequent or appropriate a use of the piccolo in the orchestrations of his contemporaries. Rossini didn’t only use the piccolo to give brightness or greater sonic range to the orchestra, he used it as a soloist, just like the other woodwinds. In Semiramide, we find perhaps the most complete and convincing example.

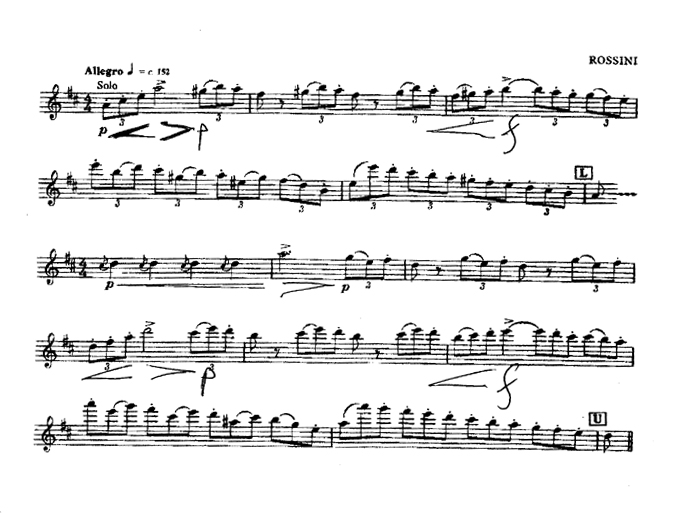

We will analyze the second theme of the first allegro (example 1) and the two truly solo passages (example 2).

A theme is heard, played by the violins and flute, which is then taken by the piccolo which repeats it. Refined and brilliant as the flute is, by doing so, Rossini brightens and refines the theme even more.

Here, neither the piccolo nor the flute is a soloist, so first of all, it would be a mistake to play loud. The piccolo is used not to contribute a solo passage, but to add color and sonic breadth, so keep the dynamic level minimal.

Since the piccolo plays one octave above the violins, I recommend:

a. A delicate dynamic

b. A light sound

d. A small opening between the lips

e. Using less air but at a high speed - don’t forget to blow with enough pressure, or you will play flat!

f. Using a light staccato while thinking of the repeated F# as one long note. The piccolo does not require a short staccato because it is a brilliant instrument to begin with!

The notes of the fourth beat of the bar are not easy. To facilitate finger coordination, I recommend applying exercise 2. of De la Sonoritè, p. 16 (example 3).

If we play only the principal notes of the first six bars, the basic melodic outline will become clear (example. 4). Even if Rossini had written these bars in piano, I think that in order to bring it to life, it would be helpful to apply some reasonable dynamics, especially during an audition.

The dynamics in Rossini overtures are inconsistent, due both to the use of different editions or to various conductors’ musical choices. This problem also involves the phrasing and even the instrumentation in certain passages as we shall see later. When playing in an orchestra, you must respect the conductor’s decisions, but at an audition, you must demonstrate your own musicality! Piccolo players are musicians, so we are entitled to and occasionally, we are obliged to interpret with some freedom for the sake of a good performance.

In the passage in which the piccolo doubles the violins, (measures 5-10 after G)I recommend phrasing in three groups of two measures.

Play a small crescendo in the first measure (measures 5, 7, 9 ) to the half note on the first beat of the next measures (6, 8,10). In order to create direction and enhance the phrasing, place a small accent at the beginning of each half-note and diminuendo to the note on the second beat.

An octave between D3- D2 is formed by the last note of the first phrase and the first note of the following phrase. The tendency of the D3 is to be too flat and that of the D2 is to be too sharp. Too small an octave will result if you do not take the trouble to adjust the pitch of each note. Even though they are not part of the same phrase, this interval must be treated with great care as the ear links the two D’s.

Perfect Intervals must be played perfectly! In measure 2, there is an ascending perfect fourth between the A2 – D3. A descending perfect fifth is found in measure 4. Make sure these are in tune with each other!

The following rhythmic pattern (measures 6-10) can also result in difficulties if you do not anticipate and prepare for them. The three staccato sixteenths that follow the sixteenth tied to the quarter are likely to be played late and for this reason, rushed. Do not fall into this trap! I recommend practicing this passage by removing the tie and articulating all four notes of each group of four sixteenth notes.

Again, when not playing in the orchestral context, I recommend moderate dynamics to create a more interesting performance. Play the passage starting at the end of measure six with more presence than at the beginning, but in the second tempo of bar 10, a sudden (subito) pianissimo will sound gorgeous – just make sure your pitch does not drop as a result of playing softly. The subito piano will serve as the beginning of a sensational crescendo.

Make sure the C#2 in measure 8 is not low as that is its tendency!

The two truly solo passages are the same theme, repeated a perfect fourth higher the second time. However, in the collections of orchestral excerpts that I have seen, these two passages have different dynamics or articulations.

Torchio has unusual (but interesting) slurs and dynamics. The Peters Edition is marked forte, Trevor Wye marks it piano.

Let’s try to understand why and solve the riddle so we can play these passages as artistically as they were meant to be! The clues are found in the orchestration!

In both passages, the piccolo is really alone only in the last three bars.

The first time, the theme is played for three bars by flute and oboe, the piccolo then takes over for the flute for two bars, remaining alone for the following three bars.

The second time, the piccolo plays for three bars with the clarinet, then, for two measures with the flute – and for the remainder, it is alone.

I think that a crescendo increasing to a forte in the last bars is a good idea and that these dynamic enhancements (example 5) create more interest, especially at an audition where you want to stand out - as a good musician!

One last recommendation: this is light, brilliant music -have fun, but without exaggerating!

Don’t play overpoweringly!

Use a clear and vital sound and - DON’T RUSH!